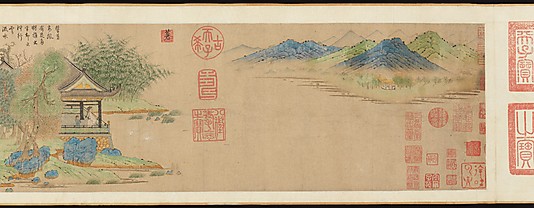

Many of the paintings evoke the scholar/gentleman at a pavillion lost in the mountains, contemplating nature, like this one, Wang Xizhi watching Geese.

They are a depiction of the refined good life, devoted to cultural accomplishment, and taking pleasure in simplicity and beauty and nature. It is a compelling vision.

But such paintings also frequently reflect a desire to find seclusion or peace in a very troubled world. The painting dates to around 1295, during the Yuan Dynasty established by Mongol invaders. Kublai Khan had destroyed the Southern Song Dynasty in the 1270s, and whole generation of scholar-officials had to come to terms with the loss of their world. This is a continuing theme throughout Chinese history of officials - selected by examination on the Chinese literary classics - seeking retreat from the intrigues of court or the corrupting practicalities of administration.

Sometimes the opposite problem occurs. There is a room in the exhibition which is focused on literary gatherings, including a scene of high officials gathering to look at paintings.

This, Elegant Scene in the Apricot Garden, depicts an actual meeting in 1437. It is a peak of cultural elegance and refinement, and power. But, as the museum write-up explains, there was a drawback.

Isolation and decline followed.One of the primary social functions of a Chinese garden was to serve as the setting for literary gatherings where like-minded friends might celebrate the season, enjoy music, or view rare antiquities, afterward composing poems to commemorate the event. Elegant Gathering in the Apricot Garden, attributed to the court artist Xie Huan, documents a historical event that took place in Beijing in 1437. On that occasion, nine of the most powerful officials in the realm gathered to enjoy painting, poetry, and other refined pursuits. Rather than be portrayed wielding emblems of political or military power, these men chose to emphasize their standing as scholar-gentlemen, highlighting the fact that, in China, status derived from one's command of cultural accomplishments.

These same men were also responsible for calling a halt to Admiral Zheng He's voyages of exploration, thus underscoring their belief that inward-oriented self-examination was more important than outward-looking exploration. Surrounded by oceans and deserts, and countries whose cultures they regarded as inferior, they saw China as a great walled garden, sufficient unto itself.

There is a deeper point here. I was talking yesterday about the difference between "classical" and "modern" views of the good life. The classical view, according to Suits, confined intrinsic value to activities that only an elite could reach, like discussing philosophy - or sitting elegantly in the apricot garden. The modern view is more "democratic", simply valuing the process of playing games rather than particular ends.

So here we have a depiction of the problem with elites - they become self-satisfied and static and inward-looking. Their values and virtues tend to become corrupt.

Here, the picture is elegant and refined, but ultimately closed and empty and contemptuous of others.

This is so often the problem with trying to aim for higher levels in society. Elevation often turns corrupt or inert. Aristocracies or merchant princes turn into rentiers. Any respect for achievement declines as the elite turns rancid.

But the "democratic" view has its problems too, of vulgarity and anomie and cruelty, as we also saw this week with the nasty celebrity gossip industry.

Egalitarianism is often incompatible with flourishing or development. By default, there is no recognition for anything except wealth and power and glamor, because any other distinctions are illegitimate or ignored.

I was thinking about what led us to live in New York back in January ( apart from being able to go see exhibitions like this at the Met).

New York represents a kaleidoscope of experience and stimulation - freedom to do new things. But as a society we haven't decided whether we want to use freedom to do new things, or what it means for us.Is it freedom from we want here in New York, or freedom to, in Isaiah Berlin's old phrase?

Maybe that's the phase transition. We've had a century where we have - slowly and painfully - evolved institutions which deal with freedom from - want, hunger, violence, scarcity. But we haven't really begin to get our heads around the next stage, freedom to.

This is our current picture of the good life, perhaps.

No comments:

Post a Comment